The theme of this year’s conference was building performance into organizational culture in Europe. Presentations covered various case studies or approaches dealing with the need to increase competitiveness in the face of continued global economic pressure, and how best to improve existing job design, work processes, and organizational systems. For a small conference, there was amazing diversity in the participants – more than 40 nationalities were present. It was a little disappointing to see US speakers getting half of the air-time, though there was a concerted effort to work the lessons from existing American models into evolving European models rather than just advocate US-centric approaches. America is, after all, only America, and despite what most Americans may believe, its business culture is as unique and un-exportable as any other culture.

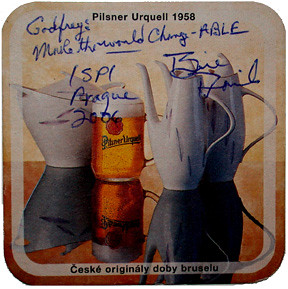

That said, there were many fascinating inputs from American and Canadian speakers that fuelled much discussion both in session and later over large glasses of Pilsner Urquell. Bob Evans, Director of IT Operations at France Telecom did a keynote on how he was brought in to build performance into the organizational culture of the France Telecom Group, demonstrating that often it takes someone perceived as a “crazy outsider” to shake up a calcified culture that is so habituated to its own stagnation it cannot see the advantages of change. In similar vein, Bill Daniels (author of Change-ABLE Organisation, one of the most useful books on change agentry I have ever read) talked about overcoming cultural resistance to performance improvement. His emphasis, which resonates with my ongoing focus on large-scale strategy, was on looking beyond individual performers to the system as a whole.

Other presentations covered a surprisingly broad canvas, with case studies from several eastern European countries providing a lot of practical insight into the performance challenges and solutions in developing nations.

Among the luminaries that I was delighted to get to know during the Prague meeting were Roger Kaufman, who has published an impressive 38 books on various aspects of performance improvement and is one of the most fun people I have ever spent time with at a conference; Tony Marker and Linda Huglin from Boise State, who had done some interesting work on the state of research in the performance improvement field; Mary Norris Thomas of the Fleming Group, who could be the next Celebrity Researcher; Bob Carleton who is probably the practitioners’ practitioner but shares my concern that research is moving too much toward cookery book replication and too far from rigorous case-specific craftwork; and John O’Connor of O’Connor Consulting in the UK, who spent many years earlier in his career where I grew up in Zambia (small worlds getting ever smaller). What impressed me about every conference participant that I talked with was their candour and their grounding in reality – the last thing you would expect from an organisation whose publications set very high standards and often read like doctoral theses.

Bob Carleton, Bill Daniels, and Timm Esque and his wife enjoying dinner in Prague.

I can recommend unreservedly ISPI’s European conference to anyone involved in performance improvement in their own organisations. It is a really intimate meeting where you can easily know who’s who and get to hang out and share experiences with anyone of interest – and everyone was of interest. You know you have been at a well-managed event when you look back at it and can’t quite work out how you had so many worthwhile conversations with so many people in so few days. Perhaps a key factor was that there were no vendors there, or at least none that made themselves conspicuous.

I have pretty much had it with the vast 8,000 plus conferences that I used to find so stimulating, and now prefer much smaller more focused events where you are more likely to find yourself among peers and “conferring” is more likely to happen. ISPI Europe is definitely on my calendar for next year.